Luis Cruz Azaceta is an award-winning artist whose works have been exhibited and included in numerous collections worldwide. Being a Cuban-born who left the island in his early years to settle in NYC made him also and expat teenager.

I believe that young Luis didn’t have much of an idea of how this particular event would shape his future then – neither in a good nor in a bad way – but in the way only expats get to know with time: the challenge of having to re-invent the self in order to accommodate the many contradictions arising from the culture shock, or what many simply call “to adapt”. But most expats know that it’s not that simple. Specially young Luis, who soon after relocating to the Big Apple was about to receive the “artist” call that will give a purpose to his future, and will eventually enable him to catalyze his experience through art. Today, fifty something years later his artworks can be seen in collections such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) both in New York City, just to drop some names readers may want to see, but actually, his success goes beyond prestigious institutions and exhibitions, and truly manifests in Luis’ ability to record his life-time experiences in his artworks with a fiery honesty. Trajectories is the name of his latest exhibition, on view at Pan American Art Projects here in Miami, and to welcome Luis back, Miami Art Guide wanted to have a brief conversation with him about his personal trajectory from being an expat teenager in New York City to becoming a renown international artist.

Francis Acea: New York must have made quite an impression on the young Cuban kid. Do you think the fact that you arrived in NYC instead of staying in the nowhere-land that Miami was then may have influenced your decision of becoming an artist?

Luis Cruz Azaceta: No question about it. New York City greatly influenced me becoming an artist. It formed me as an artist. The city’s energy, lights, intensity was awe inspiring. It was a place full of possibilities and hope.

I was 18 years old when I left my family and flew to New York. I remember seeing the lights, skyscrapers, and bridges from the plane – it brought a sense of wonderment I think I related to the high energy of the city. Three days after my arrival, I started working in a factory with my uncles. Living with them in Hoboken, New Jersey and traveling through the Holland Tunnel to the factory in Brooklyn was exciting. I was fascinated by the underground life in the subways, tunnels, etc. At night I went to learn English and American History.

Working in factories for 7 years – first the trophy factory (Brooklyn) and then the Button Company Factory in Manhattan (I was living in New York – Astoria Queens with my aunt and sister – who came a year after me) – I got fired due to union affiliation in 1962 at the trophy factory. I found myself collecting unemployment for 3 or 4 months – a lot of time on my hands. Actually this brake was important for me because it gave me time to think about my future. I spent two weeks in Times Square watching movies every day. Finally, maybe out of certain boredom of not knowing what to do, I started drawing. I always liked to draw when I was a kid. I felt pretty insignificant in such a big metropolis of 8 to 10 million people and not really knowing the language properly filled me with a need to communicate. It created a necessity for expressing myself and for creating an identity. I drew people on subways, drew in Central Park and set up still lifes at home to draw.

I went on an interview to the Button Co. The Jewish owner was there and noticed I had a book under my arm. He asked what I was reading – I said Renoir in Spanish and he smiled and corrected the pronunciation in French. He hired me on the spot because I think of the book in my hand. Working in the button factory during breaks fellow workers came to me and paid to have their portrait drawn. I remember that I even sold 3 or 4 paintings there.

I’ll never forget the first day I was in an art store buying paint and art supplies. I was in Eagle Art Supplies on 42nd Street when someone came running in screaming: “The president has been shot!” Nov. 22, 1963.

After 3 years of drawing and painting on my own, I decided to take night classes at a Queens adult center in Astoria. They had figure drawing classes. It was there that Andrew Pinto, an instructor – looked at my work and said I had talent. He told me I should go to art school and suggested The School of Visual Arts in the city. I told him that I couldn’t because of my day job at the factory – he then suggested that I apply for the night classes at SVA. He wrote me a letter of recommendation. I submitted a portfolio of work and I was admitted! First semester I went part-time at night but I knew that I had to go full time – especially at this school where very famous Contemporary artists taught – Leon Golub, Robert Mangold, Dore Ashton, Mel Bochner, Laurence Winer, and Carl Andre among others. I quit my factory job and my good friend, Ivan Acosta (a film student at NYU who later wrote El Super – a play that was then brought to film – first film dealing with Cuban and Puerto Rican immigrants living in NY) got me a part-time working in NYU Library. Second semester at SVA I went full time which I continued till graduation – 1969. I was awarded merit scholarships for my work. New York gave me the foundation and direction and opened up possibilities… like attending The School of Visual Arts that directed my future. The mecca of contemporary art was experienced through gallery exhibitions, museum shows, etc.

FA: I cannot imagine what it would be for a Hispanic artist to look for a space to show art in NYC during the sixties and seventies. What was your experience then?

LCA: I think that during the ‘50s and ‘60s the doors were totally closed – many Latin artists tried to break through but it was next to impossible. The Puertorican Institute was an alternative space for Latin artists, as well as other Latin venues. Marlborough Gallery and other uptown galleries showed Latin Masters like Matta, Tamayo, Botero, etc. – they didn’t live in NY and were very established artists in their respective countries. I don’t know whether the contemporary Latin artists of that time were limited by only being able to show in Latin venues or perhaps limited because their work did not speak to a contemporary NY scene – as they came as artists from their respective countries. The first two Latin artists to crossover were Rafael Ferrer and Juan Gonzalez – both showed in Soho at the Nancy Hoffman Gallery. They were both in the flow of contemporary art. Rafael Ferrer did inventive, daring installations using new materials such as car tires, maps, large kayaks, etc. Juan Gonzalez did photo realism (cutting edge style of that period) paintings – his work depicted memories of Cuba that created a sense of longing and melancholy. As an SVA student I thought it was important to see their work. It gave me hope and tenacity to pursue and become in a way the third Latin artist to cross over.

It was extremely hard for a Latin artist to get a gallery in Manhattan. I spent five years after graduation producing multiple series of works, developing my own iconography and visual language. In 1975 at 32 or 33 years old, I decided to make a list of galleries with Allan Frumkin Gallery being top of the list. I started at the top. I didn’t follow normal procedures – walked into Allan Frumkin Gallery on 54th Street carrying rolls of work. Allan almost ran me out but luckily he was curious to see what I had rolled up. He asked to see the work and then a big smile came across his face and asked me my name. He gave me my first solo show in 1975. I became the third Latin American artist to breakthrough and show in a blue chip gallery in Manhattan.

FA: I myself disagree with the geographical denominations on top of artists names and productions, but it seems to be true in the long run. Do you consider yourself an expat artist? How this condition may have impacted your work?

LCA: I can’t consider myself an expat artist because I was not an artist when I left Cuba. I became an artist after I was in NY. However my idiosyncrasies are very Cuban. My work has been bi-cultural – informed both by my experiences living in the U.S. and by my Cuban experience as exile. Allan Frumkin didn’t care if I was Latin or not – he was very interested in my work perhaps because it addressed urban violence and the city. In fact the first work he saw was the beginning of the Subway Series – which were primarily cut out canvasses of subway cars showing humans turning into animals… someone getting stabbed while the rest of the riders read the NY Times. I was in both worlds but without a country. Other Latin artists could return home and represent their countries in biennials, etc., but I had to carry my country in my head. In fact, in some works from the ‘80s I depict myself carrying the island of Cuba.

Of course discrimination exists but I never allowed that to effect me. Early on when I showed outside the U.S., I was seen as a Latin artist from NY. But then I had to wonder if I was a NY artist why was I not shown in a Whitney Biennial of American Art? De Kooning, Rothko, and others of the NY School were considered NY artists even though they were born outside the U.S. Lucas Samaras, Larry Poons are other examples. Somehow Europeans are never placed in a drawer. In my case, at times being Latin would allow critics to say I work with hot colors because I was Cuban. Ha! My favorite came early on in my career when I had a review by the Village Voice critic who called me “Loose Screws” playing with my name. Ha! Then a NY Times critic called my work “apocalypto”. Ironically, this worked in my favor as it called attention to my work. My dealer thanked them.

FA: Your work is plenty of transitional references, many with political resonance. Do you credit your “expat” experience for incorporating these references into your work? And ultimately as an eye opener to issues of social relevance?

LCA: My work tends to focus on the ills of society – the human condition. Perhaps the late ‘50s violence in Havana – bombs going off in cinemas and stores, shoot outs, etc., focused my vision towards the urban environment and made me aware of the fear and psychological feeling of threat. Using body parts, decapitations, dismemberment, canabalism, etc. – all seen in my work from the ‘70s and ‘80s were fueled by this early experience.

In early works like Bloody Day (1981) I painted a small self portrait figure in the foreground with the city of NY being rained upon my a slew of bloody body parts falling from the sky. In City Painter of Hearts (1981) there is the NY skyscrapers in flames with a tiny self portrait figure in the lower right corner with an easel painting a heart. Tough Ride Around the City (1981) depicts a large decapitated self-portrait head with another tiny self portrait figure riding the head like a float – parading around the streets witnessing all the atrocities. All these works were primarily an existential fictional laboratory of violence perhaps perceiving some psychological fear or threat.

In 1984 the Metropolitan was the first major museum to acquire my work and place it with new contemporary acquisitions in an exhibition called The Age of Anxiety. Artists in this exhibition included Salle, Schnabel, Clemente and Fischl. My work, The Dance of Latin America depicts dismembered body parts surrounded by oppressive military stripes with barb wire – referring to Latin American dictatorships. In the current show at Pan American, works like 911 WTC and The Terrorist continue to address the notion of urban violence.

Throughout the years my work has dealt with balseros. Cuban Odyssey (1980) – a series of triptychs done in different media – based on the Mariel experience. Journey (1986) is a large painting where an isolated self portrait figure is engulfed in the middle of the ocean. These series of works I titled Journeys and Crossings. El Botecito (1987) depicts a small boat crammed with figures lost in a field of ocean waves. Works in the current show that continue this theme: Tub: Hell Act (2009), and perhaps, the Swimming to Havana series – which is the ironic journey where those in the island want to leave and those of us out want to return – becomes a full circle where we never meet. Other issues addressed in series of works include: The Aids Epidemic Series, Terrorism, Catastrophes, War, Dictators, Homelessness, Racism, Aliens and the Border.

FA: It’s been a long time since you arrived in the U.S. However, there are still recurrent references to Cuba in your works. Have you experienced identity conflicts? Is there a place you call home?

LCA: The place I call home is a given place I call EXILE – neither here nor there.

FA: Last but not least, and I think every artist has one: do you have a definition for Art?

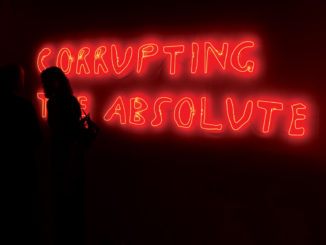

FREEDOM

FA: Thanks very much.

Be the first to comment