Taking a line from a Zen koan as her title and starting point, Elvia Rosa Castro reflects on the art of Enrique Martínez Celaya.

The Jack Shainman Gallery is one of the most multicultural, multiethnic, and inclusive galleries I know. Among the artists represented there are Nick Cave (USA), El Anatsui (Ghana-Nigeria), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (London), as well the Cubans Yoan Capote and Enrique Martínez Celaya. In 2015, Enrique Martínez Celaya opened Empires: Sea & Empires: Land, his first solo show at the Shainman Gallery. The exhibition included impressive installations and large-format paintings.

Sea-Land, Land-Sea is a children’s game that consists in jumping from one “empire” to the other (or remaining in the same place) when one player calls a command to jump. This shuffling about between sea and land, from the unfathomable to the finite, from certitude to the mysterious, is found in all of Martínez Celaya’s work as a metaphysical treatise on human existence.

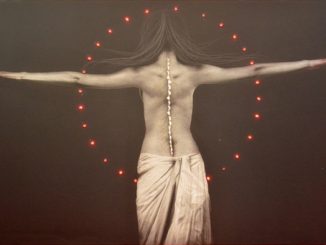

Enrique Martínez Celaya, The Bloom for the Wilderness, 2015. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery

Martínez Celaya was born in 1964, 90 kilometers from Havana, but grew up in Spain and Puerto Rico and has lived in various US cities. There, he wrote me, he first became aware of “the past as a depository of hopes and dreams, as well as the inevitability of unrealized aspirations.”

The painting The Prodigal Son and the installation El caminante / The Traveler are works Empires: Sea & Empires: Land that contain two elements seen in all of Celaya’s artistic trajectory: the house—always drawn with the same architectural design—and the suitcase, the stay and the voyage. The nomadic stay as substance of his and our lives. The temporary home, the house that flies away.

Enrique Martínez Celaya, The Prodigal Son, 2015. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery

Martínez Celaya is a latter-day descendant of Leonardo: a doctorate in physics, an artist, educator, writer. Planted within him, as in the ancient Greek gymnasium or the culture of the Samurai, are virtue and genius. The modern dream is complete, and comes apart, in him—a Renaissance man with a fractured identity. It is a condition that he will perpetually carry with him. His first drawings, he says, made when he was 10 years old, were a conscious effort to make sense of life.

This spring, Martínez Celaya returned to the Jack Shainman Gallery with an exhibition of paintings under the title The Gypsy Camp. As in all of his work, he grappled here with themes of loss and uprooting, of sadness and melancholy, not as mere attributes of existence but as existence itself. [See the Cuban Art News interview with the artist about this show.]

Installation view of Enrique Martínez Celaya: The Gypsy Camp with partial views of, at left, The Gypsy Camp, 2017, and The Landlord, 2017. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery

One of the artist’s intellectual mentors, Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), is categorical on this topic in The World as Will and Representation:

“Each being […] carries the burden of existence in general […] in a world such as we see, governed by contingency and error, finite and ephemeral, and created for sorrow […]. If we wish to know the worth of a man morally considered in his totality, we have only to consider his destiny also in general. That destiny is nothing more than need, misery, pain, torment, and death.”

Those lines from the German, sharp and harrowing, find fertile soil in Martínez Celaya’s biography (and in our own as well, even though we don’t know it), traversing his work from beginning to end. When we stand before the work, its impact doesn’t derive from a showy display of painting marked by an academic discipline, but from its capacity to wrench the soul. These paintings, which rise above all reality, suspended and immovable—precisely because they don’t pretend to be representative—are a portrait of our moral world. (The archetype plays a key role.) This is the source of their impact and their appeal.

Enrique Martínez Celaya, The Last Harvest, 2017. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery

Celaya is one of the few artists who have avoided correlations, the “conviction of the scene,” precisely because his work is unbiased in the sense that it is devoid of ego, revealing the illusory character of the individual embodied in each of us. It strikes us because suffering and pain are universal; we endure them and transcend them. In one of his most beautiful works, dramatic and compelling, the hunter suffers, or shares in the suffering of the other—in this case, a bird. The hunter hunted. The Hunter is a treatise on compassion.

Enrique Martínez Celaya, The Hunter, 2016. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery

In Celaya’s work, this avoidance of the phenomenal or this illegibility of the real suggests a new condition referring to the quality of the abstract—to draw back the veil, to go beyond a point in space and time (Malevich found something similar). Even though his works seem figurative, they contain abstraction as a principle—much like the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, which refers to the unfinished and inconclusive, to the insignificant and the evanescent. The artist is so far from references that his art lacks them, yet paradoxically contains them.

Describing another of the essential themes of his poetics, Celaya explains: “To speak of ‘regret’ is another iteration of my interest in the complex emotions generated by the past; ‘nostalgia’ is yet another. Regret is the tendency to consider the past as a place of refuge—whether because of the struggle with questions of failure, bad decisions, or our vulnerabilities and weaknesses.

Enrique Martínez Celaya, The Unloved, 2016. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery

“Much of what my recent work seeks to do is to understand the emotions related to unfinished tasks, roads not taken and, as death seems to be approaching, to learn to be humble. The inevitability of regret, even though we have to continue towards the future—as I grow older—seems to be something less clear for me.”

These scenes of immense, unearthly, lost, frozen, and desolate atmospheres, as if coming from Doctor Zhivago, make us think of an art of suspicion. They contain the most legitimate tension to which we can aspire: the struggle between free will and determinism, between manifest destiny and the freedom involved in the artistic gesture.

Enrique Martínez Celaya, The Lantern, 2017, left, and The Angel of Frost, 2017. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery

Be the first to comment