By choosing these seven artists, whose work in terms of concept seems disparate, Mosquera hopes to emphasize a lateral movement toward denarration and the dialogue created between their works. The exhibition as a whole does succeed in having an ambiguous narrative flavor; it feels almost as if the works are related in some vague way and that as the viewer you are trying to connect the dots to some elusive story. But the work of each artist individually also presents a separate array of possible outcomes, and most offer some fragment(s) of their own fabricated tales.

By choosing these seven artists, whose work in terms of concept seems disparate, Mosquera hopes to emphasize a lateral movement toward denarration and the dialogue created between their works. The exhibition as a whole does succeed in having an ambiguous narrative flavor; it feels almost as if the works are related in some vague way and that as the viewer you are trying to connect the dots to some elusive story. But the work of each artist individually also presents a separate array of possible outcomes, and most offer some fragment(s) of their own fabricated tales.

Viewers are immediately confronted with Jorge Perianes’ installation and works. Using landscapes, flora, and lonely little houses as a starting point, Perianes presents a scene of destruction that may not be so unfamiliar to Miami: realistic bugs on the walls in between and on paintings traverse the works that are riddled with holes. Walls, collapsed on each other in a domino effect, are surrounded by sawdust and have window scenes boarded up with actual lumber and nails. Entire paintings and bits of wall are “chewed” completely apart. This plays to the show’s idea (viewers witness the end result of a narrative via the fictionalized destruction of the art and story itself) and in many ways sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition and functions much like a staging.

Less readily apparent is the relationship Tracey Snelling and Rodrigo Facundo’s work has to narrative or the deconstruction thereof. Both artists employ a larger sense of subtlety; Snelling, who is represented by PanAmerican, creates micro-worlds that distantly call to mind the miniaturized model of the town in Tim Burton’s “Beetlejuice.” They have a similar down-and-dirty twist, and are buzzing with tiny flashing neon signs and jumbled sound; complete with a peppering of pop-culture video clips and references. They again present a staging of sorts, but because of the scale, feel more like objects or relics that preserve the same continuous moment in a dioramic manner. Facundo’s encaustic pieces break down into bare-bone structures the anatomies of actions and settings – almost like the blueprint of a narrative. Similar to Snelling’s works, they feel like more subtle, diagrammatic fragments that relay a single moment in a story.

Video art seems to face an additional challenge when it comes to the idea of denarration – there often a kind of intrinsic expectation, however conscious, of linear time indicating some kind of forward-moving narrative. And there is also in equal part its antithesis; whether it is repetitious, textured, or purely visual-experiential video work. To an extent, the three video pieces in Denarrations are neither and both; perhaps this is what sets them apart in Mosquera’s mind from other contemporary video works, or at least effectively exemplifies this particular thesis.

Aernout Mik’s silent panning landscape work, Osmosis and Excess, which was shown in conjunction with several others of his videos at the MoMA in Manhattan earlier this year, centers around three simultaneously occurring visual events that independently taken tell their own vague stories. But when combined – it’s difficult to detect a beginning and end but it’s clear that something is happening – they relate like strange parallel universes that through visual coincidence, overlap. The toy cars the children are playing with in the mud – which is also the contradictory floor of an odd, third-worldly pharmacy – relate to the impressively expansive river of cars in the unexplained landscape, which is a backdrop for children on a hilltop hitting piñatas. There is a certain tension in viewing and waiting out the long video that is not really resolved or explained as it rolls on, despite the quasi-political comments Mik hints at. In this, it is both storytelling and solely pictorial.

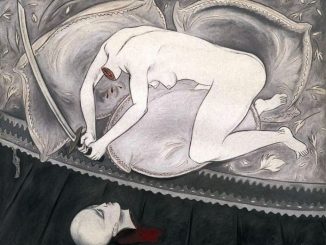

Nina Yuen’s video, Alice, is also both lovely to look at, and also a disjointed, at times backward narrative. As the event takes place – a slowly unraveling suicide with several garbled actions that lead up to it – she as the voiceover narrator eventually becomes the subject; a bit like how Vonnegut himself enters into his own storyline in Breakfast of Champions. This synthesis makes the story self-contained, and causes it to cannibalize itself; twisting the intensity of the narrative into oddity. Using a bleak palette and slow reversal shots of a falling dress and other moving textures, the piece communicates a melancholy fiction that holds even though the reality of the story collapses in on itself when, by the end, the character is also the narrator so her death no longer makes chronological nor realistic sense. The weightiness of the subject also holds, even though the small details are distorted; this piece in some ways feels like the most straightforward citation of denarration in the grouping.

Cristina Lucas’ piece takes a departure from the other videos for obvious reasons. First, the subject matter is more confrontational (not to mention is it projected onto the ceiling and therefore viewed by looking skyward); and although this largely places the focus on the visual aspect, time does carry on in a more linear manner. A naked female performer against a night sky vista, holding a paintbrush in her vagina, squats on top of a transparent surface and slowly paints the words “big bang” using only the dexterity of her hips. Denarration, it seems, is in some ways more apparent in her work when viewed as a whole; she addresses political and scientific issues and re-configures them – creating a new history through a feminist lens. This context helps to bridge the connection between the show’s title and “Big Bang.” In making both an allusion to Courbet’s painting (which is difficult not to point out, given it seems a crucial part of the work), The Origin of the World that offers a similar view of the female anatomy but implies a very different sentiment, and modern cosmology – a science she views as traditionally very male-centric – Lucas creates a redux not only concerning the history of the universe and its beginnings, but women’s role in it. Her narrative lacks the feeling of fiction the others possess, which presents a different perspective on denarration.

Vibeke Tandberg also delivers her short and nonsensical allegory in a sequential manner. What exactly it represents is unclear, despite any consumerist or feminist implications that may be lurking in the title – Princess Goes to Bed with a Mountain Bike. The large photographic series – a format and method she often uses to examine or realize an object or situation, Tandberg places a cheaply disguised figure, herself in this case, in a non-descript bedroom and allows a fairly absurd tidbit of a tale unfold. This paper-bag princess of sorts skips courting the bicycle and takes it straight to bed and it seems to end there. Is it saying she needs not a man? Does it reveal her secret lust for simple machines? Does that in-and-of-itself say something? Or is it mostly just nonsense, and in being so, sort of anti-narrative? With all the lingering questions it imposes, it is effective in making viewers feel like there is something more – whatever that may be.

There’s a sense that there is some kind of narrative that consistently evades you, or that elements of a story are re-arranged, missing, or out of order that permeates the exhibition as a whole, and lies at its core: if you were able to perceive any one narrative in its entirety, then the phenomenon of denarration would break down. The term itself is fairly obscure. It’s like hearing anecdotes from someone else’s life anachronistically over years and years – you begin to sew them together, regurgitate them, re-arrange them until you have a dull, hazy image of these events that were real for them, but imaginary scenarios for you. Denarrations leaves you with the debris of obliterated narratives that have been put back together, cleverly edited by artists. But sometimes it’s the absence that tells the story.

Be the first to comment