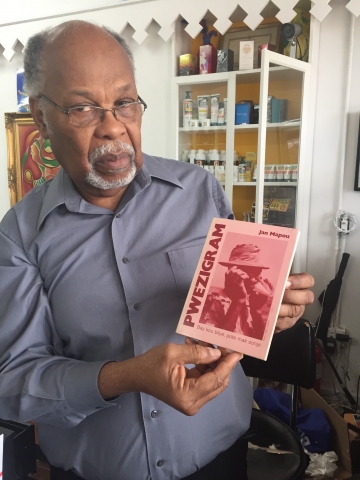

In 1990, Jan Mapou, the Haitian playwright, poet, and activist, rented a booth at the Caribbean Marketplace in Miami’s Little Haiti neighborhood. He set up 300 books, mostly in Creole, from his own private collection: books on Haitian history, folklore, religion, politics; romance novels and big, colorful children’s stories by Haitian authors. The “Haitian boat people” — as they were known in the US — had been arriving to the US since 1972; that term belongs in a story of its own. “Boat person” is both nondescript and guileless; it’s also a euphemism. Never mind that the regime from which they were fleeing was cruel; Haitian immigrants were met with governmental pushback and the development of a racist, xenophobic mythos: that they were voodoo practitioners, carriers of disease, and stole Americans’ jobs.

Mapou, however, knew that Haitians and non-Haitians alike would want to know about the history of the island, its people, their traumas and, more importantly, their artistic contributions. He set out to rewrite those spiteful myths by showcasing and preserving other, truthful narratives. You can have a taste of this at the Little Haiti Book Festival, part of the larger Miami Book Fair, taking place this coming weekend.

Back in Haiti, Mapou was co-founder of Mouvman Kreyòl Ayisyen, a group of writers, artists, and teachers who fought to implement Creole as the primary language in Haitian schools — that the school system’s predominant language was that of its colonizers (French) contributed to rates of illiteracy. For this, he was jailed by the Duvalier regime. Mapou also helped develop Sosyete Koukouy (Society of Fireflies), a group of writers who exchanged their Creole literary works. In the spirit of Sosyete Koukouy, Mapou, once settled in Miami, eventually moved the contents of his booth at the Caribbean Marketplace into a store, Libreri Mapou, on the neighborhood’s main drag (Northeast Second Avenue), where he has spent spent years hosting theater and choir performances, readings, and meetings.

Today, Little Haiti, which became a bastion of the Haitian community, is becoming rapidly gentrified. Moreover, many of its residents are losing their Temporary Protected Status (TPS). Funding for small arts organizations in the area is minimal, but Libreri Mapou still stands. On weekends, neighborhood families, writers, tourists, and artists traveling from Haiti crowd the shop.

I spoke with Mapou at his shop in anticipation of the Little Haiti Book Festival, which each year enlivens the neighborhood and restores the sheen that never really diminished.

Monica Uszerowicz: The Little Haiti Book Festival is coming up soon, right?

Jan Mapou: Yes. Its goal is to show our neighborhood, our people. The comments our president made about people from the Caribbean and Africa — they hurt everybody. He has no heart. If I can make an introduction to the plight of the Haitians: it’s terrible. We’re on the verge of losing Little Haiti to gentrification, first of all. And though it’s a good time for all Haitians to get together, to show evidence of our culture, these poor people — especially the artists — are forced to leave, to seek refuge or sanctuary cities. By July, as you know, all those who were under TPS have to leave the country.

MU: These political changes will affect the neighborhood directly.

JM: Definitely. The situation forced a great majority of Haitians in this area to go into hiding. Some of them are born here or have family here. I understand that security for the country is a priority, but you cannot destroy people’s lives like that.

Furthermore, there are no refugees coming to replace those who are getting old. After the young people here finish school, they don’t return to Little Haiti. There’s no replenishment of the community. And gentrification is coming forcefully: developers buying the major corners, raising the rents, forcing renters onto month-to-month leases, getting rid of them when they’re ready.

MU: Community developers often claim to promote “the arts.” But Haiti and Little Haiti both have their own creative communities.

JM: When I opened Libreri Mapou in 1990, it was not only to showcase, but to preserve our culture. We had a booth at the Caribbean Marketplace, and I exhibited about 300 books on history, culture, religion. The city of Miami had given money to an organization called the Haitian Task Force, which helped to create some economic development for Little Haiti. At that time we were not welcome. All kinds of rumors were associated with us — that we were bringing voodoo, or AIDS, or killing people. A lot of Haitians left New York and Canada to come here and help. I left New York in 1984, feeling that there was a need. Scholars and other people, including non-Haitians, wanted to know about Haiti. There were questions being asked.

MU: Were you sharing books from your own private collection?

JM: Yes, I used to sell books in New York. I created an organization in Haiti in 1965 called the Creole Movement — Mouvman Kreyòl Ayisyen. That little booth was very successful. People were happy to read, to understand Vodou, to understand our heart, our problems. When I heard a house was for sale here, I bargained with the guy and bought it, and transported the booth. People love it.

Bookstores are being closed; they say people don’t read anymore. But there’s another phenomenon: while people read less, authors are still producing books. You’re a reporter — you have something to say, you don’t care if somebody is going to read it. That’s what’s inside of you. You want to get it out for, maybe, the next generation. Writers and authors will sometimes invest their own savings in publishing books, knowing that nobody’s going to read them! There’s hope in that future.

MU: You’re a writer, too.

JM: I’m a playwright. After my studies, I was in Port Au Prince. My organization was having meetings at night, discussing the Haitian language: Creole. Statistics show about 65% of the Haitian population are illiterate. The real cause of that: we’re using a heritage language, not the mother tongue of the population. Creole is our language. But it wasn’t included in our curriculum in school — only French. So we started writing, trying to promote the use of Creole: we wrote articles in Creole; I had a radio program on one of the popular stations in Haiti, Radio Caraibes. We kept pushing the government to introduce Creole in the classroom.

MU: What happened?

JM: On April 6, 1969, the Duvalier army arrested 12 of us and took us to Fort Dimanche, a jail in Haiti that’s a type of gulag. If you check out, it’s a miracle; you’ve got to thank god. The way they treat you there is not for a human, nor for an animal. Because I’m a devout Catholic, I prayed a lot. I prayed to Santa Clare—she’s a good one for any problem you have. She’s celebrated on August 12. On August 11 I stayed on my knees all night, praying, “Santa Clare, I was trying to help my people. Please get me out of here.” On August 12 at noon, they opened the door and let me out. In 1971, I left Haiti and came to New York, then to Florida in 1984. Our organization, despite all these problems, didn’t die. We kept it alive. There were chapters formed in Haiti, Canada, New York, Miami, Connecticut, Cuba. The society is Sosyete Koukouy: “Koukouy” is “firefly.” We’re lighting up in the darkness.

MU: Illuminating the dark.

JM: Exactly: the light of education, of life. In Haiti, the people suffer, or are still leaving for a better life somewhere else. That’s why I’m here, why I opened the store: to preserve our culture, to help the Haitian writers producing books, to get an audience — to help the young Haitians born here, who know nothing about their culture or their history in Haiti.

MU: Little Haiti Book Fair started with Sosyete Koukouy, too.

JM: Yes. We used to do a lot of activities around here — dance, theater, choir; I even produced one play a year. This place used to be packed. But unfortunately, after 2008 — the economic situation we had here in this country — they shut down most of the grants they’d give to small organizations like mine. So we got a small grant from the Miami-Dade Department of Cultural Affairs and partnered with the Miami Book Fair International.

The book fair is really a festival. We’ve got workshops on dance, music; panels; Haitian cuisine; folklore; games for children. This year, Edwidge Danticat and Jacqueline Charles from The Miami Herald are in conversation. This is also an opportunity to introduce the panel the next day — a panel on women. Women are so busy: they’ve got their children, their work — and they still find a way to write! Women are rising and shining, everywhere. If you need a good novel, find a woman writer.

MU: Do the young white artists or developers come here? Do they participate in the neighborhood?

JM: In my opinion, and based on several meetings I’ve participated in, they’re just taking advantage of Haitian culture. For them, it’s an introduction to let the Haitian population to know that they are coming to help them. I went to a stakeholders’ meeting; they were discussing whether they’re going to keep the name Little Haiti or change it Lemon City. Then a guy, one of those developers — big cigar in his mouth — said, “We’re not here to discuss ‘Little Haiti’ or ‘no Little Haiti.’ We’re here to discuss what we are going to do. The name will come after.” When you hear something like that — it hit me right in my heart. These people come to do their own business.

We’re not against development or modernization. We know someday, something has to happen. But respect the people living there, their culture, their history, their culture. In the 1980s, Haitians were coming almost every morning, dying in the sea. We strive. We’re still fighting. I keep fighting. There is a history here. That history — we cannot step on it.

The Little Haiti Book Festival takes place on Saturday, May 5 and Sunday, May 6 at the Little Haiti Cultural Complex (212 NE 59th Terrace, Miami) and at Libreri Mapou (5919 NE 2nd Avenue, Miami).

Be the first to comment